Unraveling the mystery of superconductivity at high temperatures, specifically in copper oxide materials, remains one of the most puzzling challenges in modern solid-state physics. But an international research team of engineers and scientists may have taken one step closer to understanding.

Superconductors are materials that gain unique physical properties when cooled to extremely low temperatures. They stop resisting an electric current, allowing the current to pass through freely without any loss of energy. Superconductors are used in technologies such as MRI machines, electric motors, wireless communications systems and particle accelerators. While thousands of examples of superconductive materials are known to the scientific community, many questions remain about why and how superconductivity occurs. New research may provide an answer.

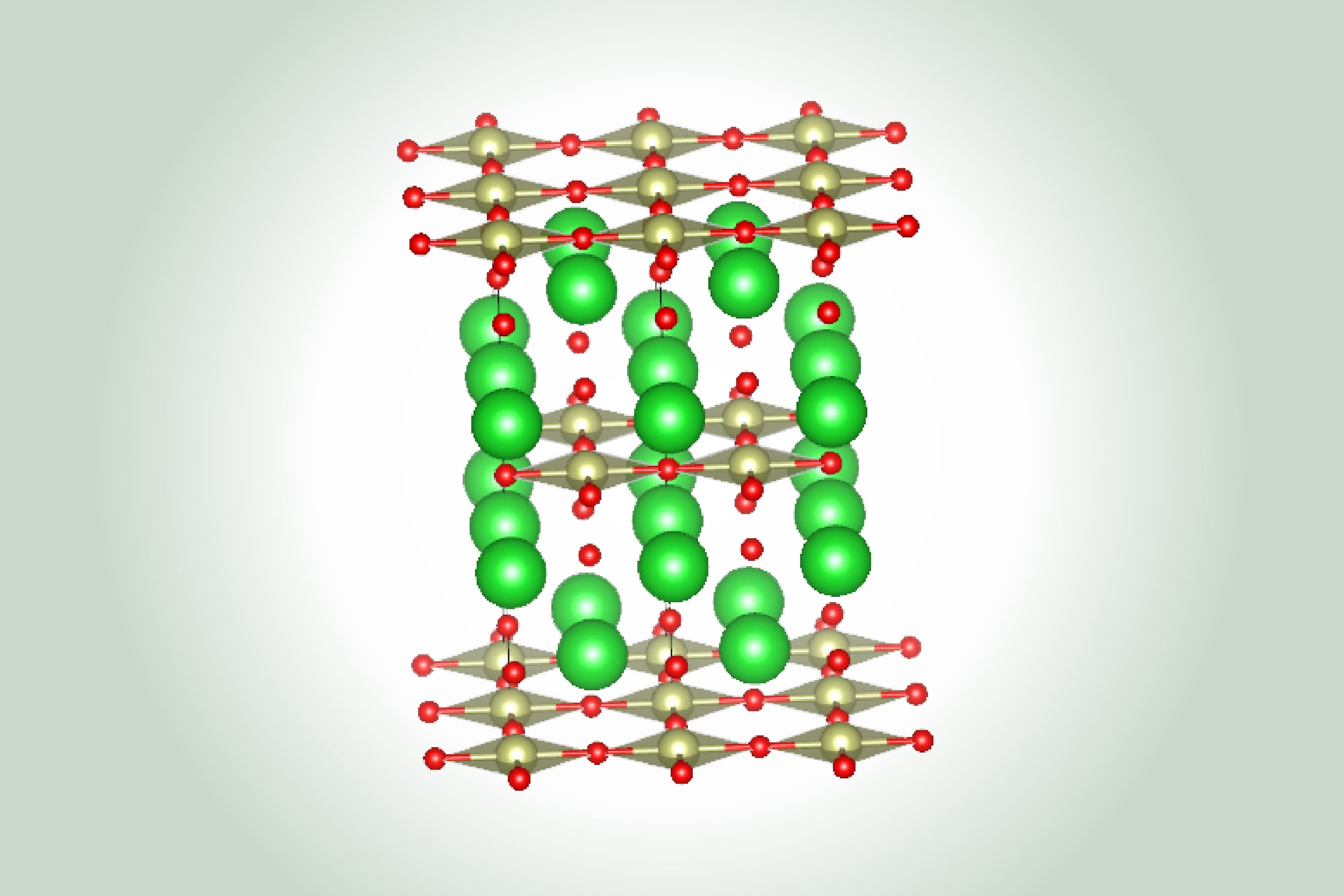

A research team that includes Jianshi Zhou, research professor of mechanical engineering in the Cockrell School of Engineering and a member of The University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Materials Institute, has confirmed the existence of a phase transition at a temperature close to absolute zero degrees, higher than the temperature needed for many superconductors, in copper-oxide-based (or cuprate) superconductive materials. The team believes that it could be during this phase transition, the “quantum critical point,” when superconductivity actually occurs. The findings were published in a recent issue of the journal Nature.

The study measured the effects of heat on two cuprate systems known to be superconductors: Eu-LSCO and Nd-LSCO, both copper-oxide-based crystal systems. The two materials were cooled to their critical temperature points while large magnetic fields were used to suppress their superconductivity. The resulting thermodynamic signatures produced through the experiment confirmed the existence of the “quantum criticality” phase in the examples analyzed.

“‘Quantum criticality’ had been proposed as one potential factor for facilitating superconductivity in cuprate systems,” Zhou said. “Our study confirms this to be the case.”

Zhou is the only U.S.-based researcher on the study and one of a handful of engineers worldwide with the expertise to grow and analyze cuprate crystal systems, one of the most commonly used superconductors.

Engineers often classify materials based on their resistance to the flow of electric currents. This is a property measured by observing the behavior of electrons. Metals like copper — a key component in wires connecting our smartphone chargers, microwaves, light bulbs and more to power outlets – are made up of electrons that move freely around its atomic structure. This offers weak resistance to electric currents, a property that makes for a strong conductor.

Resistance, no matter how weak, is unwanted in conductive materials as the energy used to resist converts into heat and is technically wasted. In a perfect world, cables would be made from a material with zero resistance to electrical current. This is where superconductors come in. However, because all known superconductors must be cooled to extremely low temperatures, they are difficult to use regularly in practical applications. Ultimately, engineers and scientists worldwide continue to search for superconductive materials that can be used at much higher temperatures, hoping to reach room temperature. Each discovery made takes researchers one step closer.

“Understanding why these materials become superconductors will lead us to this holy grail of room-temperature superconductors,” Zhou said. “It’s only a matter of time, hopefully.”

This research was funded by Canada First Research Excellence Fund, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Science Foundation and MEXT in Japan.