New Red Cross Partnership Will Bolster Humanitarian Engineering Program

The University of Texas at Austin and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) have inked a partnership that aims to solve challenges in humanitarian response through engineering innovations.

The partnership formalizes an alliance that dates back several years. It will bolster a growing humanitarian engineering program led by Janet Ellzey, professor in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering in the Cockrell School of Engineering. And it gives IFRC the facilities, resources and know-how of one of the top engineering schools in the nation to create solutions for technical challenges to serve refugee camps, rural communities and other areas in need.

“This partnership provides us with on-the-ground knowledge, experience and information,” Ellzey said. “In this area of working with marginalized communities, one of the most common criticisms is that the people doing the design work lack awareness of the situation on the ground.”

The partnership remains in early stages, but the two sides are already aiming big. They envision engaging companies, other foundations and universities to tackle big problems in the global south. Recently, the IFRC approached the Kenyan Red Cross Society regarding their interest in a collaboration with UT-Austin.

“When you look at the big problems the planet faces, things like climate change mitigation and response, it’s an all-hands-on-deck situation,” said William Carter, a Texas Engineering alumnus who focuses on water and sanitation for IFRC. “We are going to need more engineers who are able to bring their skill sets to solve these problems.”

Ellzey envisions opportunities to send students abroad to work with communities where IFRC has a presence. And she sees it as a mutual learning experience, where the engineers can contribute their technical skills, and they, in turn, can learn about community needs and skill sets.

The partnership could allow for the expansion of the program to encompass several other disciplines beyond engineering, including health and social sciences. Ellzey mentioned building a field lab that could give students a better idea of the opportunities and limitations available to underserved communities.

The seeds for the partnership were planted when Carter, who received his B.S. in civil engineering in 1999, read about Projects with Underserved Communities, a program Ellzey started with professor James O’Connor from the Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering more than a decade ago. The two got in touch briefly about the program, but nothing came of it initially.

Later, a group of students wanted to start developing products to help underserved communities. Ellzey liked the idea but didn’t know what kind of products were needed. She got back in touch with Carter to get a better sense of demand on the ground.

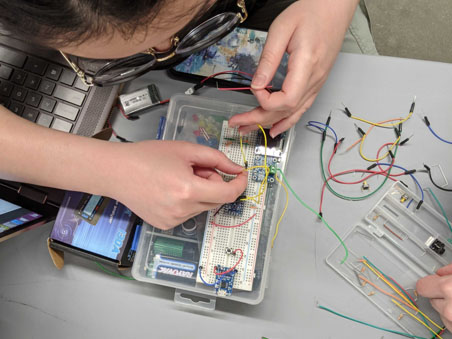

Though the product design course is only in its second year, students have already built numerous products to help underserved communities. They include:

- A device to fabricate menstrual pads for women in refugee camps

- A biodigester that converts latrine waste into fertilizer

- A device to remove water from latrine waste, enabling it to dry faster

- Compact, solar-powered lighting systems for refugee camps

This track record of results in such a short time persuaded IFRC to formalize the partnership with Ellzey and the humanitarian engineering program.

“We’ve shown this is not all theoretical,” Carter said. “We have demonstrated the ability to work together at field level.”

This partnership isn’t the only avenue Ellzey is pursuing to grow humanitarian engineering at UT Austin. She was recently named a Jefferson Science fellow. During the yearlong fellowship, Ellzey will be embedded at USAID, one of the largest aid organizations in the world.

Ellzey has a history at UT Austin of developing programs to expand the horizons of engineering students. In 2004, she created International Engineering Education, which develops study abroad programs for engineering students. Five years later, in 2009, in collaboration with James T. O’Connor in the Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, she launched Projects with Underserved Communities, a three-course sequence in which teams of engineering and social work students partner with rural communities around the world to solve technical challenges facing those communities.

In 2017, she launched a Certificate in Humanitarian Engineering. A year later, she began working with Carter and students to create the product design class.

When Carter graduated from UT Austin, he wanted to take a different path than most engineers might, so he went to Honduras with the U.S. Peace Corps. After that, he spent time working for organizations in Iraq, Ethiopia and Chad before joining the IFRC. He is the IFRC’s global focal point for water and sanitation in emergencies, and he earned a master’s degree in public health from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine along the way.

Ellzey and Carter share the opinion that exposing engineers to the world’s most important problems early will make them more thoughtful in their work, whether they end up at a huge tech company, a construction firm or a humanitarian organization.

“Not every student who goes through this program will make a career in humanitarian engineering,” Ellzey said. “This practical experience will benefit them wherever they go. And they will come out of it with a larger view of the world and its needs.”