The gold standard for removing benign skin cancers has been around since the 1930s. Although very accurate, it requires a full laboratory next door to the procedure room to determine whether the full tumor has been removed or not. A research group at The University of Texas at Austin is aiming to make that process more efficient and potentially expand access to this type of surgery to a broader population.

The current procedure, known as Mohs micrographic surgery, involves cutting out tissue, analyzing it with a microscope to look for tumors to determine if parts of the tumor remain in the body, which would mean going back and cutting out more tissue. While highly accurate, the procedure is time-consuming – each round of tissue removal involves additional time for analysis – and requires highly specific equipment and training that poses logistical challenges for patients who don’t live close to major medical centers.

A new $2.7 million grant from the National Institutes of Health will support a collaborative project between the Cockrell School of Engineering and Dell Medical School at The University of Texas at Austin to improve on the Mohs procedure and make it more accessible. Additionally, the researchers aim to take this approach and implement it in other types of cancer surgery where it can’t be used today.

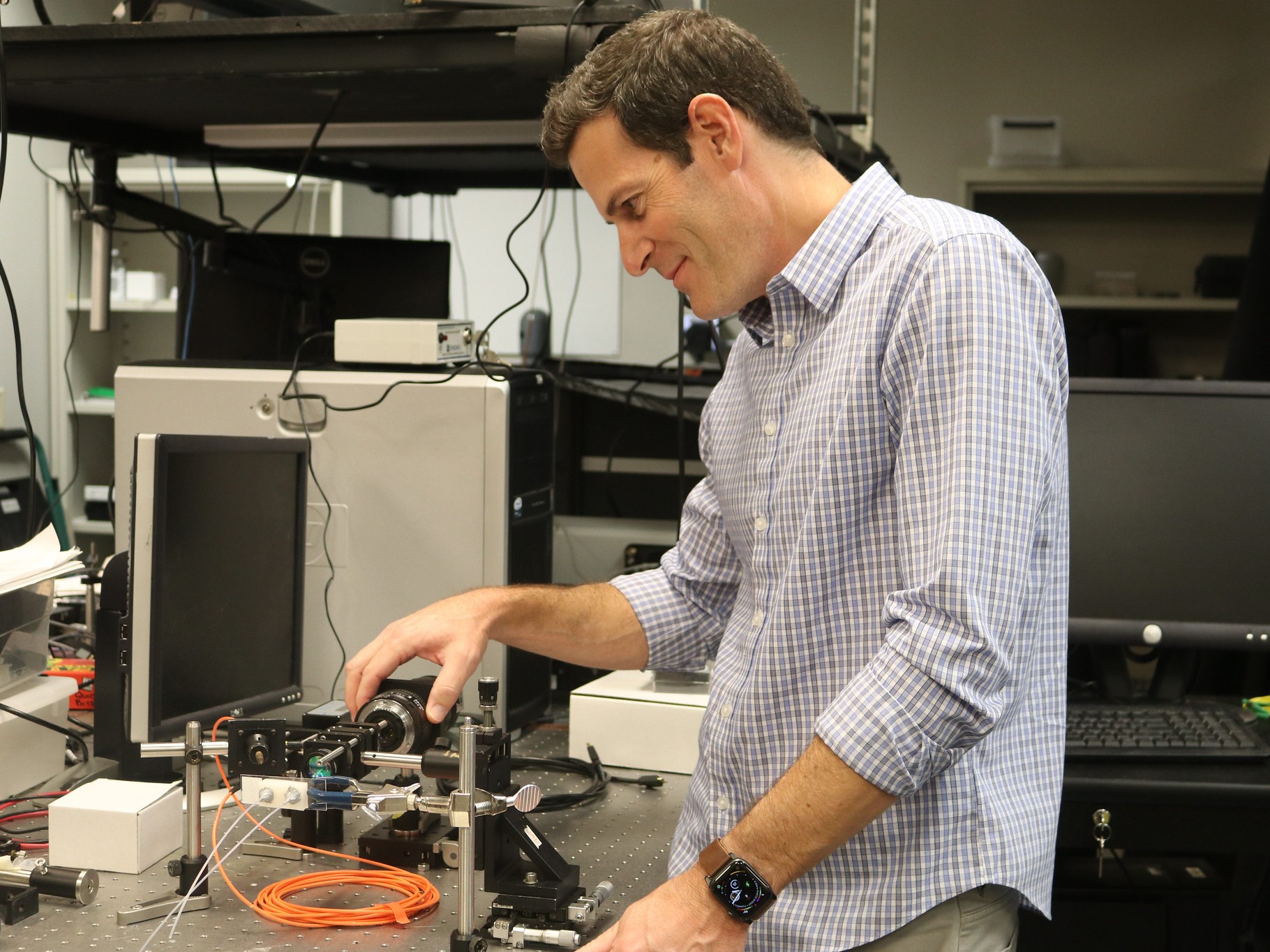

“Reducing the infrastructure burden of the current procedure could improve the patient experience and expand the patient population that has access to this highly accurate surgical approach,” said James Tunnell, an associate professor in the Cockrell School’s Department of Biomedical Engineering.

The team plans to create a box-shaped device that is equipped with cutting-edge microscopy tools and machine learning capabilities and can image and analyze a tissue sample in a matter of minutes. The surgeon quickly gets the information they need to know if they’ve gotten the entirety of the tumor, or if another round of tissue removal is needed.

Mohs surgeons typically complete a year-long fellowship in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology, which includes significant time with histology — the study of tissue structure using microscopes. The surgeon is in charge not just of removing tissue, but going back and forth to the lab to analyze it.

The main thing the surgeon looks for is if there are any parts of tumor on the margins, or edges of the sample. If those edges have any tumor cells on them, it’s an indicator that a piece of the tumor remains in the body, and the surgeon has to go back and take out more tissue.

“We look at the entire periphery and the base of what has been removed,” said Matthew Fox, a Mohs certified surgeon, chief of the Division of Dermatology & Dermatologic Surgery, associate professor Department of Internal Medicine at Dell Med and one of the leaders of the project. “Think about a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup, we are analyzing the wrapper that holds the chocolate and peanut butter.”

Each round of analysis takes time, and the surgeon continues the process until there are no more tumor cells at the sample margin. This happens all while the patient sits and waits in an outpatient facility.

The device the researchers are developing would do the analysis itself, making the process more efficient and with potentially broader accessibility.

Mohs surgery was developed as a treatment for skin cancer as this type of cancer is typically readily accessible to the surgical team and can be removed with local anesthesia alone. If the principles of Mohs surgery can be replicated with this device efficiently, and simplified in the way the researchers envision, it could be applied to many other types of cancer and its level of accuracy could be replicated elsewhere.

“More accurate identification of tumor margins during surgery may reduce additional surgeries and treatments,” Tunnell said.

Also part of the team are Mia Markey, a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering focused on biomedical informatics; Tyler Hollmig associate professor of dermatology and Jason Reichenberg, professor of dermatology at Dell Med and Brian Hobbs, associate professor of population health at Dell Medical School.