UT Mourns Lithium-Ion Battery Inventor and Nobel Prize Recipient John Goodenough

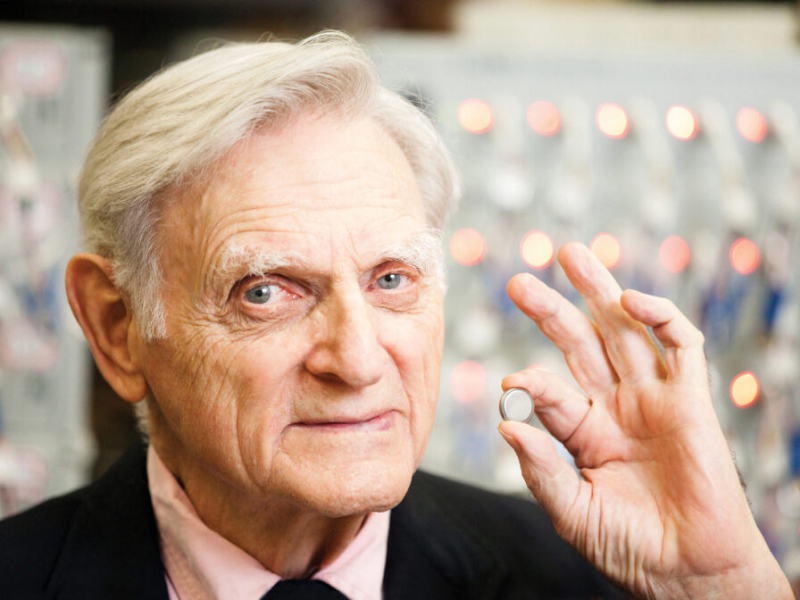

John B. Goodenough, professor at The University of Texas at Austin, who is known around the world for the development of the lithium-ion battery, died Sunday at the age of 100. Goodenough was a dedicated public servant, a sought-after mentor and a brilliant yet humble inventor.

His discovery led to the wireless revolution and put electronic devices in the hands of people worldwide. In 2019, Goodenough made national and international headlines after being awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for his battery work, an award many of his fans considered a long time coming, especially as he became the oldest person to receive a Nobel Prize.

“John’s legacy as a brilliant scientist is immeasurable — his discoveries improved the lives of billions of people around the world,” said UT Austin President Jay Hartzell. “He was a leader at the cutting edge of scientific research throughout the many decades of his career, and he never ceased searching for innovative energy-storage solutions. John’s work and commitment to our mission are the ultimate reflection of our aspiration as Longhorns — that what starts here changes the world — and he will be greatly missed among our UT community.”

John Goodenough received the Nobel Prize in 2019.

Goodenough served as a faculty member in the Cockrell School of Engineering for 37 years, holding the Virginia H. Cockrell Centennial Chair of Engineering and faculty positions in the Walker Department of Mechanical Engineering and the Chandra Family Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. Throughout his tenure, his research continued to focus on battery materials and address fundamental solid-state science and engineering problems to create the next generation of rechargeable batteries.

John Goodenough enjoyed working closely with students.

“Not only was John a tremendous researcher, he was also a beloved and highly regarded teacher. He took great pride in being a mentor to many graduate students and faculty members who benefitted from his wisdom and encouragement,” said Provost Sharon L. Wood. “The world has lost an incredible mind and generous spirit. He will be truly missed among the scientific and engineering community, but he leaves a lasting legacy that will inspire generations of future innovators and researchers. I am honored to have known and worked with John.”

Goodenough identified and developed the critical cathode materials that provided the high-energy density needed to power electronics such as mobile phones, laptops and tablets, as well as electric and hybrid vehicles. In 1979, he and his research team found that by using lithium cobalt oxide as the cathode of a lithium-ion rechargeable battery, it would be possible to achieve a high density of stored energy with an anode other than metallic lithium. This discovery led to the development of carbon-based materials that allow for the use of stable and manageable negative electrodes in lithium-ion batteries.

“John was simply an amazing person — a truly great researcher, teacher, mentor and innovator,” said Roger Bonnecaze, dean of the Cockrell School. “His joy and care in all he did, and that remarkable laugh, were infectious and inspiring. What an impactful life he led!”

John Goodenough speaks at Energy Week at The University of Texas at Austin.

Born in 1922 in Germany, Goodenough grew up in the northeastern United States and attended the Groton School in Massachusetts. In 1944, he earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Yale University. After serving as a meteorologist in the U.S. Army, Goodenough returned to complete a master’s degree and Ph.D., in 1952, both in physics from the University of Chicago. At the University of Chicago, he studied under Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi and John A. Simpson, both of whom worked on the Manhattan Project. His doctoral adviser was renowned physicist Clarence Zener.

Goodenough began his career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory in 1952, where he worked for 24 years and laid the groundwork for the development of random-access memory (RAM) for the digital computer. He emerged as a pioneer of orbital physics and one of the founders of the modern theory of magnetism, which became known as the Goodenough-Kanamori Rules. These rules provide a practical guidance in the research of magnetic materials and have a huge impact in developing devices in telecommunications.

John Goodenough at Oxford University in 1982.

After MIT, Goodenough became a professor and head of the Inorganic Chemistry Laboratory at the University of Oxford. During this time, he made the lithium-ion discovery.

He came to UT Austin in 1986, setting out to develop the next battery breakthrough and educate the next battery innovators. In 1991, Sony Corp. commercialized the lithium-ion battery, for which Goodenough provided the foundation for a prototype. In 1996, a safer and more environmentally friendly cathode material was discovered in his research group, and, in 2020, a Canadian hydroelectric power company acquired the patents for this latest battery.

“John’s seven decades of dedication to science and technology dramatically altered our lifestyle, and it was truly a privilege to get to work with him for so many years,” said Ram Manthiram, professor in the Cockrell School who was a longtime friend and associate of Goodenough’s and joined him at UT in the 1980s. Manthiram, a battery pioneer in his own right, delivered the Nobel lecture in Stockholm on behalf of Goodenough. “John was one of the greatest minds of our time and is an inspiration. He was a good listener with love and respect for everyone. I will always cherish our time together, and we will continue to build on the foundation John established.”

A celebratory symposium in honor of John Goodenough’s 100th birthday brought in battery and energy experts from around the world.

In 2022, in honor of his 100th birthday, scientists and engineers in the global battery solid-state science communities came together on the UT Austin campus for a symposium to share stories of Goodenough’s impact and discuss challenging problems in condensed matter physics and chemistry and the next generation of battery research.

Goodenough’s quick wit and infectious laugh were defining characteristics that influenced the level of fame he received. That laugh could be heard reverberating through UT engineering buildings — you knew when Goodenough was on your floor, and you couldn’t help but smile at the thought of running into him.

He was still coming into work well into his 90s. For him, there was no reason not to. “Don’t retire too early!” Goodenough told the Nobel Foundation and others. It was advice he frequently gave and certainly followed.

John Goodenough receives the 2011 National Medal of Science from President Barack Obama.

Goodenough, who never had children of his own, was passionate about giving to the University. He frequently donated the monetary prizes from his awards to UT, helping to support engineering graduate students and researchers. In 2006, he established the John B. and Irene W. Goodenough Endowed Research Fund in Engineering, and in 2016, in honor of his wife, Irene, he established the Irene W. Goodenough Endowed Presidential Scholarship in Nursing. In addition, St. Catherine’s College at the University of Oxford established the Goodenough Fellowship in chemistry in his honor.

Among his many recognitions, including the Nobel Prize — which he was awarded jointly with Stanley Whittingham of the State University of New York at Binghampton and Akira Yoshino of Meijo University — Goodenough is the recipient of the National Medal of Science, the Japan Prize, the Charles Stark Draper Prize, the Benjamin Franklin Medal, the Enrico Fermi Award, the Robert A. Welch Award, the Copley Medal and many others. He has authored several books, including an autobiography titled “Witness to Grace,” published in 2008.

Goodenough and his wife were married for over 70 years until her death in 2016. His brother, Ward, who was an anthropologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania, died in 2013.

Images of John Goodenough for media: https://utexas.box.com/s/fu6lpwq1b2ce8a8ps2of2ps2436sms2y. Unless noted in the file name, please credit images with The University of Texas at Austin.