Our power grids face more challenges than ever before, with significant weather events on the rise and cyberattacks threatening critical infrastructure.

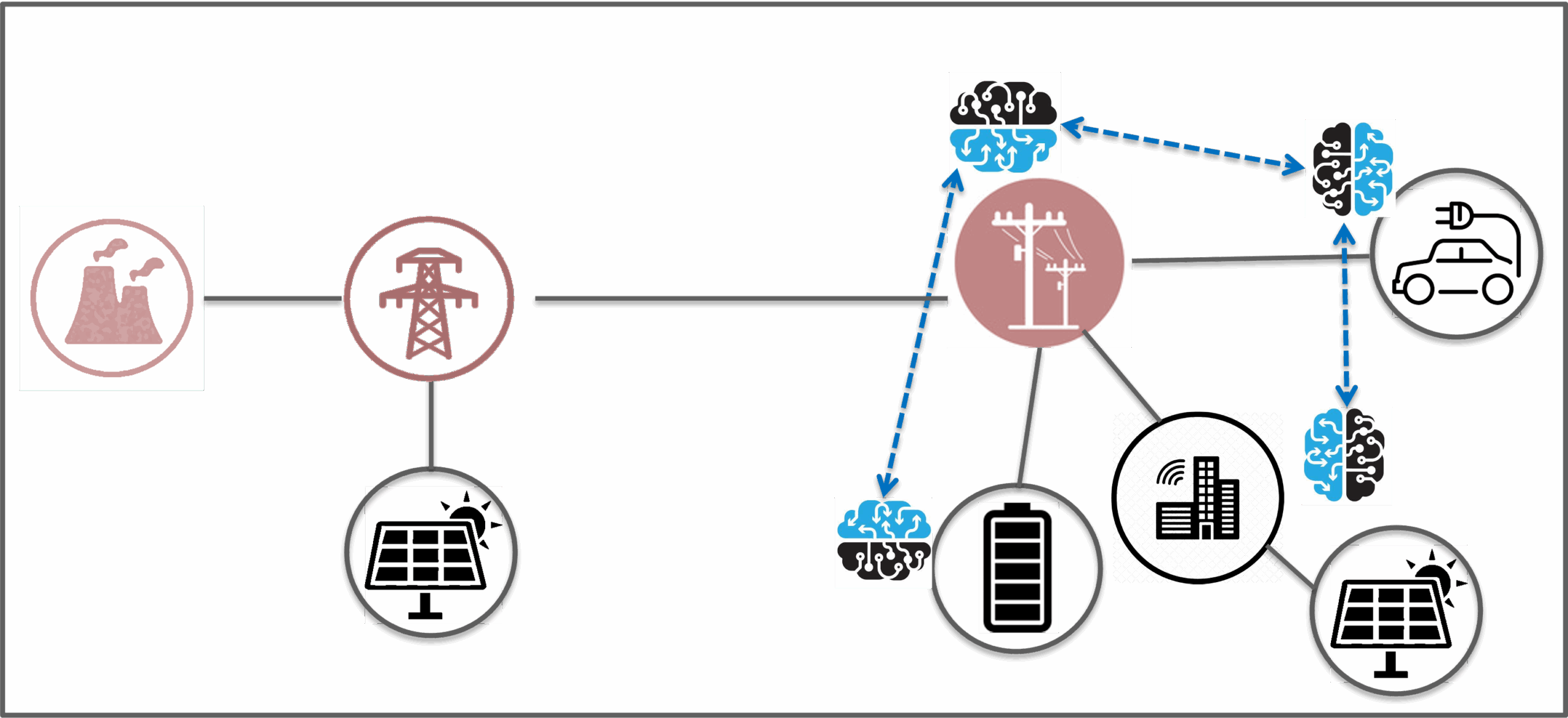

Texas Engineer Javad Mohammadi has dedicated his research to strengthening power grids, using artificial intelligence to make them more resistant to evolving threats. This involves infusing sensing and communication capabilities up and down the chain, so that the electrical grid can communicate with many connected devices that exist today, from electric cars with powerful processing units to internet-connected smart thermostat systems to networks of solar panels and wind mills.

“If you were to coordinate all these devices, that would give you an army of intelligent devices that could talk to each other and respond to emergencies,” said Mohammadi, an assistant professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Fariborz Maseeh Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering. “If the grid is in a bad situation, and there is a need to reduce energy use, all the different devices could coordinate among themselves to reduce their energy usage.”

Mohammadi’s research uses AI to get smart devices to communicate with each other, helping to build a stronger power grid.

The news: The U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research recently selected Mohammadi to be part of the Young Investigator Program. Mohammadi joins 47 other scientists and engineers selected for this year’s program, which supports high-risk research that other funding agencies might not otherwise consider.

Mohammadi, who joined the Cockrell School in 2021, focuses on multi-agent, autonomous systems and their application to power systems. Multi-agent systems involve several different types of smart devices working together to operate effectively.

Mohammadi published a paper at an IEEE conference last year focused on optimizing decision making between multiple intelligent agents, and he has several other papers in development in this area as well.

Javad Mohammadi, assistant professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Fariborz Maseeh Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering

Why it matters: In the real world, this kind of technology could, in addition to improving grid resilience, help consumers be more self-reliant. Infusing intelligent sensing and communications systems into tools like smart thermostats, generators, solar panels and more, allows neighborhoods to become microgrids. If some houses lose power, others could help out. And this independence could also help the grid in large-scale events by reducing the overall strain in times of high demand.

There are some larger issues at play that must be addressed to enable these smarter, more active grids. The smart devices playing key roles in this system are costly and may not be affordable to many potential users. And without reliable internet, or innovations that bring these communications systems on to the devices themselves, the system could struggle.

“We have to make sure we provide resources to communities that lack access, and that we design these systems around the idea that not all communities possess the same resources,” Mohammadi said.