On the morning of July 2, 1937, Amelia Earhart and her navigator were nearing the end of their longest flying stretch since the two set out from Miami a month earlier as part of Earhart's quest to be the first woman to attempt circumnavigating the globe.

On the morning of July 2, 1937, Amelia Earhart and her navigator were nearing the end of their longest flying stretch since the two set out from Miami a month earlier as part of Earhart's quest to be the first woman to attempt circumnavigating the globe.

The two were tired. They'd been flying 22 hours straight, over a distance of 2,556 miles from Lae, New Guinea to their current destination, Howland Island, a coral island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. In preparation for this long leg of the journey, the pilots shipped their luggage and souvenirs back to the U.S., hoping that the lightened load would maximize fuel efficiency of their 39-foot Lockheed Electra.

But at 7:42 a.m., Earhart radioed the first sign of trouble: Her plane was low on fuel.

She and navigator Fred Noonan thought they were approaching Howland Island, and, despite a series of radio transmissions trying to lead them to the landing strip, the two were lost.

Seventy-three years later, they still are.

For University of Texas at Austin’s 1971 aerospace engineering alum, Jon Thompson, Earhart’s disappearance has also become a near obsession and real life treasure hunt. It has kept him up at night and taken him to the depths of the ocean in search of any trace of the downed plane.

"My wife, Susan, says that she's the only person she knows that lets her husband go out searching for another woman," Thompson said.

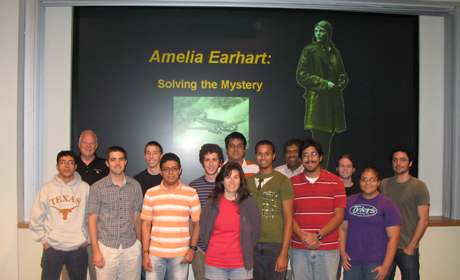

Now, Thompson is bringing the search to his alma mater, the Cockrell School of Engineering, where students will apply their engineering skills to try and help solve the mystery.

Led by aerospace engineering senior, Vishnu Jyothindran, the students will conduct a flotation analysis that examines two scenarios under the assumption her plane landed in the ocean. The first is a center of gravity study that assumes she was able to safely land the plane in the ocean by flaring the plane, a technique used by pilots to gently land an aircraft by pointing its nose upwards before touch down. The students will try to determine how far the plane would glide before sinking and then how far it would float at sea, assuming the natural half-mile drift of the ocean.

The second scenario, which Thompson says is more probable, assumes that she wouldn't have had the strength and time to flare the plane, especially given that fuel tanks would be nearly empty and all the plane’s weight would be at its front, causing it to fly at a downward, slanted angle. If the plane went down in this manner, Thompson said it would have flipped violently and broken up on impact.

Because her disappearance happened so long ago, Jyothindran said the accuracy of his and other students’ findings will be heavily dependent on how much data they are able to obtain for the two studies. Earhart’s plane was custom-made for her, so it is harder to track down records, flight drawings and weight calculations of the plane, Jyothindran said.

Because her disappearance happened so long ago, Jyothindran said the accuracy of his and other students’ findings will be heavily dependent on how much data they are able to obtain for the two studies. Earhart’s plane was custom-made for her, so it is harder to track down records, flight drawings and weight calculations of the plane, Jyothindran said.

“I’m excited about these studies because they’re different from any other project we do in school. In class, you expect you’ll get a question that you can solve with data in the textbook,” Jyothindran said. “We don’t have that guarantee here and that’s unfortunate but it’s also just reality.”

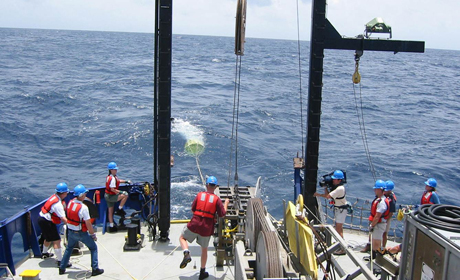

The students’ findings will be used to help Thompson and an approximately 35-member crew look for the plane when they go on their third expedition to the South Pacific sometime next year. The expedition team has already combed over 2,200 square miles of ocean bottom since 2002 and it plans to search another 400-600 square miles during the upcoming trip using sonar equipment that can detect something as small as 1 meter, even in the 18,000-ft. deep ocean where the plane is believed to rest.

Students have gone on past expeditions and Thompson said there could be an opportunity for a Cockrell School student to board their upcoming trip to the Pacific.

"I'm excited about getting the students involved with me at UT because the rest of the team [involved in the expedition] is versed in the undersea aspect but few in the group are pilots who understand the flight characteristics," Thompson said. "Therefore, they don't understand a non-feathering propeller landing and they can't grasp why she might not have been able to sit that plane down."

Thompson, on the other hand, does. A former Army pilot during Vietnam, Thompson experienced a close call while flying off the coast of Cambodia in route to Thailand in a plane similar to what Earhart flew. His plane started burning too much oil and the engine lost pressure.

"I've thought about that a million times. I think of how simple that predicament was compared to her because we knew where we were going and I knew all I had to do was turn right and we were within a few miles of land. But she didn't have that option," he said.

A hobby becomes a passion

How Thompson got hooked on Earhart is a story of its own.

From 1992-97, the Germantown, Tenn. resident worked as director of Cultural Affairs for the City of Memphis.

Thompson’s day job of securing fine arts collections from the Louvre or negotiating an exhibit on China might not have seemed like a fitting career given his background as everything from a reconnaissance pilot, owner of a multi-million dollar Caterpillar distributorship, which he’d recently sold, and former graduate student in aerospace engineering at The University of Texas at Austin.

Oddly enough, Thompson’s life of traveling prepped him for the job and he soon landed one of the largest and most successful exhibitions in the world: he brought “The Titanic” to Memphis.

Oddly enough, Thompson’s life of traveling prepped him for the job and he soon landed one of the largest and most successful exhibitions in the world: he brought “The Titanic” to Memphis.

The company that discovered the sunken ship, RMS Titanic, needed money to pay for ocean dives down to the vessel, and Thompson realized the potential for his city.

He offered to help fund the next dive if the company would put him on its board and let Memphis handle the Titanic exhibition, which, as part of the agreement, would make its debut in the city. The deal worked and it helped make a name for Thompson in the exhibition’s arena.

“We were having 3,500 people a day coming to this thing. When the movie came out three months after we opened the exhibit, the lines went to 7,000 a day,” he said.

Then, in 2000, another blockbuster opportunity came calling: Find Amelia Earhart’s plane and create an exhibition.

A phone call from his friend, FedEx founder and president Fred Smith, alerted Thompson to an upcoming expedition to the South Pacific. The search would be led by Elgen Long, a former Flying Tiger’s pilot and co-author of the book, “Amelia Earhart: The Mystery Solved,” and David Jourdan, president and founder of the Maine-based ocean exploration company, Nauticos, LLC, which has found everything from an ancient shipwreck to an Israeli submarine in water 10,000 feet deep.

Thompson was intrigued. Two years later, he was on a boat to the South Pacific.

Search takes team to the Pacific Ocean

What happened to Earhart and Noonan is clouded in both mystery and controversy. One theory is that they flew to then-uninhabited Gardner Island, some 350 miles southeast of Howland, and died there. Another alleges they were spies for then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt and were captured and killed by the Japanese.

Thompson and his team believe the more commonly accepted theory that she ran out of fuel and they’ve narrowed in on a search location near Howland that’s derived from the line of position last broadcast by Earhart. The team has made two expeditions, one in 2002 and another in 2004, but both were cut short by equipment failure or, in the last instance, a crew member fell ill.

The team is made up of everyone from engineers, navigators, technical supporters, housekeepers, cooks and members of the media. Thompson’s job on the ship is to help guide sonar along the bottom of the ocean and watch on a screen to see what its cameras detect.

During downtime, the crew often talks about the woman they are in search of.

“She may have died on impact or maybe not,” Thompson said. “Either way, it’s difficult to think about what she was going through in those final moments.”

Potential for an exhibition

Thompson no longer works for the City of Memphis, but he plans to use his experience with exhibits to showcase findings from Earhart’s plane, if and when it is found. Among the possible artifacts to be discovered are her leather aviator jacket, goggles, hat and jewelry, which he’d like to display in a traveling exhibit on a floating barge that would eventually travel to roughly 20 cities in North America.

For Thompson, uncovering the mystery of Amelia Earhart is more than a business opportunity. It’s a way to finally put to rest one of the most famous missing persons of our time.

“With all the advancements in technology, we’ve never been able to solve this and people are still enamored with Amelia because she was a great example for women around the world,” Thompson said. “She became the most famous woman in the world, but wasn’t alive to enjoy it.”