Researchers from The University of Texas at Austin are leading a team from 16 top engineering programs to establish a roadmap for hiring diverse faculty members.

The authors of the new paper in Nature Biomedical Engineering call for an overhaul of hiring processes in engineering that, despite best efforts, have failed to increase diversity. The problem, the researchers argue in the paper, is that departments “lack the education and skills needed to effectively hire faculty candidates from historically excluded groups.”

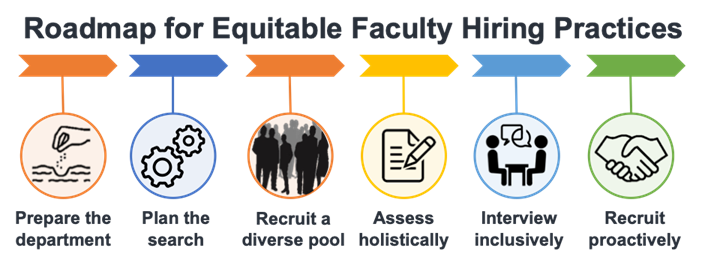

The research team details six major steps necessary to increase diversity in faculty hiring, based on evidenced-based best practices as well as experiences in their own institutions. The primary goal is to actively recruit a more diverse group of applicants and improve the rate that Ph.D.’s from historically excluded groups go on to become faculty members.

Elizabeth Cosgriff-Hernández, professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Department of Biomedical Engineering

“You can’t just say ‘it’s not our fault, we don’t get the applicants;’ that’s passing the buck,” said Elizabeth Cosgriff-Hernández, a professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering’s Department of Biomedical Engineering. “If you want to change the diversity of your hiring program, you have to change how you’re getting applicants and how you evaluate them.”

Part of the challenge is underrepresentation among Ph.D. earners. Only 4.4% of all PhD e come from historically excluded groups, according to the paper. But even if that number increases exponentially, the researchers say, there is a “conversion problem,” of getting people from these groups into faculty positions that continues to prevent the diversification of academia.

Throughout the paper, the researchers emphasize the importance of developing consistent rubrics with fleshed out criteria to evaluate candidates. The researchers cite studies showing that a lack of strict criteria leads to less diverse hiring and “sliding bias.”

For example, without strict criteria, Cosgriff-Hernández says, if a hiring manager likes someone, whatever qualities that person has can become the priority for the position. People tend to be biased toward people who they like and who are like them.

Unbiased practices like evaluation rubrics can level the playing field for candidates that come from historically excluded groups.

“We need to evaluate the person, not how well they were coached up on the applications or for interviews because then you’re just evaluating their mentoring,” Cosgriff-Hernández said.

In addition to finding a diverse pool of candidates and using rubrics to evaluate them, the researchers’ recommendations include:

Preparing the Department: Getting buy in at all levels, from staff, to faculty to leadership is key. People aren’t going to want to work in environments where they don’t feel welcome.

Plan the Search: A job search can take several months, but departments should spend significant time making a game plan for the search in advance. During that time, focal points should include making sure everyone is aligned in what they are looking for in a candidate, building a strong search committee, training them to complete the task, assessing roadblocks from past searches and revising materials to embrace new hiring strategies.

Interview Inclusively: To level the playing field, the researchers recommend being transparent about the interview process. They also advocate for including students in the process, collecting independent feedback after interviews and mitigating the impact of potentially toxic faculty members.

Recruit Proactively: Once a top candidate has been identified, they should get the opportunity to meet students and broad members of the university community. Showcasing the department and its vision and making the environment equitable in advance can increase the chance that the prospective faculty member will accept the offer.

The project spawned out of a group called BME Unite, a national network of biomedical engineers that came together in 2020 to educate themselves, improve representation and combat racism in STEM. This group has formed several sub-committees that have published papers in scientific focused on issues of bias and lack of representation in academia.

Cosgriff-Hernandez was a co-author on a previous paper published in Cell last year, calling for an end to discrimination in research funding that disadvantages Black scientists. Along with Cosgriff-Hernández, Gabriella Coloyan Fleming of UT Austin’s Center for Equity in Engineering is part of the research team.

The team members are all part of BME Unite. They include Brian A. Aguado and Karen L. Christman of the University of California San Diego; Belinda Akpa of the University of Tennessee; Erika Moore, Ana Maria Porras and Gregory A. Hudalla of the University of Florida; Patrick M. Boyle and Kelly R. Stevens of the University of Washington; Deva D. Chan of Purdue University; Naomi Chesler of the University of California Irvine; Tejal A. Desai of Brown University; Brendan A.C. Harley of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign; Megan L. Killian of the University of Michigan; Katharina Maisel of the University of Maryland, Kristen C. Maitland of Texas A&M University; Shelly R. Peyton of the University of Massachusetts Amherst; Beth L. Pruitt of the University of California Santa Barbara; Sarah E. Stabenfeldt of Arizona State University; and Audrey K. Bowden of Vanderbilt University.